The giant’s coin

One of the funny things my boy and I started to do together once we moved to the UK was to check our change for interesting coins. Because, you see, there are so many different coins here. More than 50 types of two pounds are in circulation. Each with its own story to tell to my little one.

Why does this crown have a dagger in it?

Because of some king that lived long ago – quickly read the story of Richard and turn it into a bedtime adventure …

This is a steam engine. How does this work?

Boiling water – steam – crankshaft piston – turning linear motion into wheel rotation …

This gentleman built the railway and that bridge in Bristol. Tell me more about him!?

In the background there is a strange looking bridge in Exeter…

Why is this general pointing at me?!

He wants you to learn about an important alignment design parameter called “transition shift”…

This skull is eating flowers!

Ah, yes! You will learn enough about this in school. Let’s check another coin.

Wow! Planes!

Yes. You know, during the war they were building planes also here in Swindon. But you know what they were building here? …

There was one coin he was never interested in. It seemed confusing, with so many things drawn on it, and it is also so common. The commonest of all two pound coins.

One evening, when we could not find any new coin to discuss about, he asked me to read th inscription on the edge of this common one.

And my penny dropped!

(I have tears in the corner of my eyes again, today, recalling this.)

“Oh, my boy! This is the most precious one! These common coins are about the greatest mind that ever lived! I have a few bedtime stories to tell you about him.

His name was Isaac Newton.”

“Tell me, daddy, tell me!”

Newton’s equivalent radius

What follows is partly a work of fiction…

One day, Johann Bernoulli …

“Daddy, you said his name is New Town!”

Shh! Shut up and listen! You know me, in the end it will all make sense, in some way!

So … Johann Bernoulli decided one day to challenge the greatest minds of his time. He sent them all the same letter:

You think you are smart? Solve this then:

What is the shape of an inclined plane on which a ball will move the fastest?!

Signed: J. Bernoulli (brother of the transition curve J. Bernoulli)

This letter was also sent to Isaac Newton, the giant.

But Isaac was busy that morning with finding why the rainbow colours are as they are. He solved this rainbow problem by noon.

Then he took his lunch under a tree. As he was eating, an apple fell on the ground, and Newton asked himself why do things fall down and not up.

He thought about this for quite a while and by tea time he came up with the theory that all the objects attract each other with a force proportional with their masses and in reverse proportion with the distance between them.

Then Newton had his afternoon tea. In front of him, on the table, it was the challenge letter from Bernoulli. While having the tea, he started to scribble some formulas on a tissue and solved this challenge. He sent the tissue to Bernoulli without signing it.

Then Newton went for an evening walk, thinking about the best method to torment the children who went to school. So he came up with something called Calculus. He even wrote a book about this – it has some things about curvature equivalence there.

And the night came. Newton was still quite awake, and the sky outside was incredibly clear. As this is quite uncommon here, in England, he decided to look at the stars. But you see, people then used lenses made of common glass. And the glass generates what is called chromatic aberration. The stars were not very clear, and Newton was not happy.

He thought about these aberrations for a bit and this is how he discovered what is called “Newton’s rings”. He thought of ways to get better lenses than the ones Galileo had.

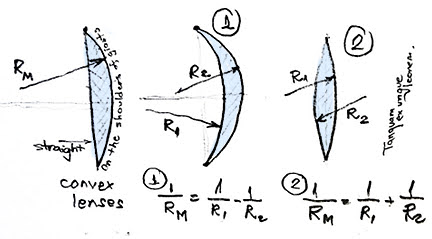

Because, you see, the lenses can have the same magnification but have different shapes, being bent in similar or contra-flexure. Depending on how they are bent, they can increase or lose those aberrations.

How did he know they have the same magnification?

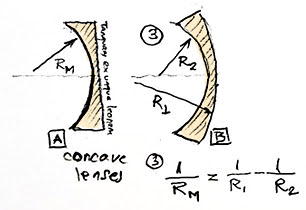

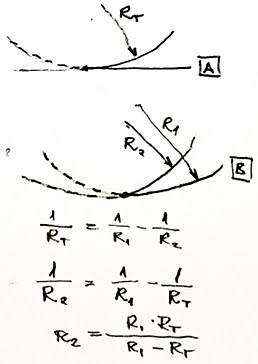

Because by then people already knew to calculate the equivalent curvature of a lens. This looks very similar to what we use today, for railway track turnouts, when we want to install them on curves. If you rotate the concave curves to horizontal they look like turnouts.

Oh, this formula was already common then – interpolations were done with it, people used to calculate the movement of the planets with it.

So Newton, using these equivalent radius formulas, imagined a few types of lenses, but it was already late so he decided that a curved mirror would be better than a lens. And this is how, that night, he invented the telescope.

Looking at the stars, he thought how gravity would work for two celestial bodies. This is cleverly called “the two body problem”. Using some proportion formulas similar to the ones for the equivalent radius, he solved this problem before going to sleep.

That night, he had a dream about the apple he saw falling during the day. In his dream, a really bad man picks the apple up and puts it on the head of a boy, then asks the father to shoot the apple using a crossbow. In this dream, Newton was the father. His name was William Tell. He was Swiss. The father splits the apple in one crossbow shot, and then he starts a revolution.

“Daddy, I don’t understand this Swiss connection?!”

“Me neither, my boy! Me neither!“

Knowing the lion by its claws

The next day, Bernoulli received an anonymous letter, with his challenge solved, and a note: “Don’t challenge me again on maths!”

Seeing how smartly the challenge was solved, using some complex equations about curvature equivalence, he said: “I recognise the lion by his claws! Only one mind can solve this problem in such a clever way! We need to have a coin in his honour!”

“Oh, I understand! That’s why we have now so many coins about this Shake Spear, isn’t it?!”

Discover more from A railway track blog

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.